Oct 8

Sparse federal data on LGBTQs is threatened by recent Trump executive orders

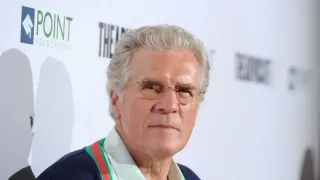

John Ferrannini READ TIME: 8 MIN.

Recent executive moves by President Donald Trump are making data collection about sexual orientation and gender identity at the national level more difficult. This could have serious implications from health care to violence prevention to policy and law, advocates noted.

It also affects economic indicators, as there aren’t as many reports that study those effects on LGBTQ people.

“It’s not like we have a long history of doing this research,” Ilan Meyer, Ph.D., a distinguished senior scholar of public policy at the Williams Institute, said in an interview. Meyer declined to disclose his own sexual orientation.

The Williams Institute is an LGBTQ think tank housed in the UCLA School of Law.

One of its briefs from earlier this year, for example, looked at changes in the Trump administration as it pertains to student loans . According to the Williams Institute brief, 2.9 million LGBTQ Americans had federal student loans during the Biden administration, and held $93 billion in loans. The Trump administration and Congress implemented various mechanisms to change the federal student loan program, the Williams Institute noted.

It noted that Project 2025, the conservative blueprint that was developed for a second Trump administration, aims to replace income-driven repayment plans with ones that have no cap on interest. As of September 29, Business Insider reported that the U.S. Department of Education is beginning negotiations on student loan repayment proposals.

In terms of SOGI, Meyer co-authored a brief earlier this year sounding the alarm, and was among scholars who filed public comment on eliminating gender identity questions from the National Crime Victimization Survey.

“We can’t start any conversation about violence prevention without knowing there is violence against transgender people, so when we are robbed of any data that can be presented to policymakers, to legislators, to judges, we’re basically back to the dark ages of LGBT research, when we didn’t have a lot of information,” Meyer said. “The January executive orders included gender, meaning that any measure of gender relating to health or any topic is no longer allowed, so that basically means we can't assess any parameters relating to transgender people. … It also included the DEI executive order.”

Meyer was referring to two executive orders from early in Trump’s second term, which started January 20. The first, Executive Order No. 14168, states that, “It is the policy of the United States to recognize two sexes, male and female” and defines sex as “an individual's immutable biological classification” and not a synonym for gender identity. This order on gender identity also prohibits federal contractors and grantees from recognizing and respecting their identities or advocating for their civil rights.

Two other Executive Orders, Nos. 14151 and 14173, terminate equity-related grants and prohibit federal contractors and grantees from employing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility principles in their work.

A coalition of LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS nonprofits sued Trump and his administration over the three executive orders. The San Francisco AIDS Foundation is the lead plaintiff, and is joined in the suit by the San Francisco Community Health Center and the GLBT Historical Society locally, as well as the Los Angeles LGBT Center and six other agencies.

A federal judge in San Francisco granted a preliminary injunction and, in July, about $6.2 million in federal grant funding was restored, according to Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, which represents the plaintiffs. The case is ongoing.

The Williams Institute’s Meyer said that on the basis of these executive orders, gender identity questions are being taken off of federal questionnaires, and questionnaires funded with federal dollars. In addition to the crime survey, these include the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (a survey done every two years for a representative sample of middle and high school aged youth) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (a survey about health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services).

On the basis of the two orders targeting DEI and equity, the National Institutes of Health canceled some grants that were for studies of the LGBTQ community. Meyer said many of these grants were paused or canceled during the heady early days of the administration, when Elon Musk was the head of the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. Musk left the federal government in May.

“Many people think those [cancellation] messages were not written by NIH staff because they were unusually written,” Meyer said. “When it was canceled, they got a brief explanation that it was about the DEI executive order. And it’s not completely clear there was consistent thinking through all this.”

Meyer has seen first hand the importance of SOGI data collection. In 2010, he was an expert witness at the federal bench trial Hollingsworth v. Perry, using empirical studies to show how same-sex marriage being illegal caused LGBTQ Americans stress and negative health outcomes due to the discrimination. After the trial, which was held in San Francisco, federal District Court Judge Vaughn Walker ruled that the Proposition 8 same-sex marriage ban was unconstitutional. Walker, who came out as gay after the trial, has since retired. A federal appeals court upheld his ruling, as did the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2013, same-sex marriages resumed in California. (They had been allowed during a brief window in 2008 before voters passed Prop 8 that November.)

SOGI data help that kind of empirical data be as accurate as possible. Studies before questionnaires began considering LGBTQ populations were often open to serious criticism because they “were not the most rigorous scientifically,” Meyer said.

“It was the CDC data that showed disparities between LGBTQ and heterosexual, cisgender students,” Meyer said, referring to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “That data is so rigorous, it could not be argued with. It could not be denied.”

The U.S. Census Bureau is among those that stopped working on gender identity questions after Executive Order No. 14168, former director Robert Santos told National Public Radio.

During his first term, Trump upended efforts to see the 2020 census gather data about LGBTQ Americans. During the Biden administration, the census bureau’s American Community Survey began testing SOGI questions about sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Results are expected in 2026. However, these plans may be in jeopardy, as back in March the Trump administration terminated the census bureau's three advisory committees: the 2030 Census Advisory Committee; the Census Scientific Advisory Committee; and the National Advisory Committee on Racial, Ethnic, and Other Populations.

The members all received notices saying Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, whose agency oversees the census bureau, had determined the committees' purposes "have been fulfilled," according to the Associated Press.

In 2024, LGBTQ data collection expert Nancy Bates, a lesbian, had been appointed to the panel advising on the decennial count of the country's population and was tapped to serve as its vice chair. Bates told the B.A.R. she had planned to advocate for the 2030 census to include the SOGI questions in order to determine how many people living in the U.S. identify as LGBTQ.

"Neither sexual orientation nor gender identity measures were likely to make their way onto the 2030 Census. However, before the EO by Trump, these two Qs WERE likely to be added to the American Community Survey," Bates had told the B.A.R. in March. "I am hopeful that sexual orientation will still be added to the ACS, but the measurement of Gender Identity now seems extremely doubtful."

State, local levels

There has been some progress collecting SOGI data in California. In 2016, Assembly Bill 959 was passed. It requires state agencies to collect demographic data on gender identity and sexual orientation as of July 1, 2018. The bill specifically instructed the departments of health care services, public health, social services, and aging to collect the "voluntary self-identification information" pertaining to LGBTQ people.

In 2024, legislators were able to secure $2.2 million in the state budget for improving data collection on the health of LGBTQ Californians.

In San Francisco, various city departments were to have started gathering SOGI data in 2016. During a hearing in 2021, however, the San Francisco Department of Public Health acknowledged problems it has had in collecting such information. It cited its switching to a new electronic records-keeping system called Epic during the 2018-2019 fiscal year and having to pivot its focus to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic as for why it has been hampered in better collecting the SOGI data, as the B.A.R. reported at the time.

In addition to DPH, the other city departments required to collect SOGI data are the Mayor's Office of Housing and Community Development; the Department of Human Services; the Department of Disability and Aging Services; and the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. The Department of Children, Youth and their Families is also required to have its grantees ask the SOGI questions of the youth they are serving.

Patchwork of data

The hodgepodge patchwork of data at the federal level makes it hard for researchers to establish firm statistics. In creating an estimate on the transgender population of the U.S. earlier this year, the Williams Institute used or extrapolated from both CDC behavior risk factor surveillance system and youth risk behavior surveillance data.

“We had to go state by state and request the data from the various state-level agencies that administer state-level YRBS data,” said Jody L. Herman, Ph.D., the Reid Rasmussen Senior Scholar of Public Policy at the Williams Institute. “We had some success. That process takes quite a bit of time, so it was a team effort and we were able to get data from a handful of states, which was enough for us to use in the model. … It does take a lot of work and time.” (Herman also declined to be identified for this piece.)

David Forte, a straight ally who is director of research translation and strategic initiatives at Opportunity Insights in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said he is able to use insights from tax and other government records “to understand what economic mobility looks like down to the neighborhood level in communities across America … down to the census track level.

“It’s super valuable in terms of understanding the landscape, but my understanding is those estimates only go down to the state level in an aggregate form,” he continued.

However, while he has very detailed data on race and sex vis a vis economic mobility, SOGI data is often “just not part of the data sets.”

“Perhaps there are statistical methodologies you can adopt to make those estimates but, from a data standpoint, the data isn’t as strong,” he said. “We just don’t have information collected in a systematically rigorous way.”

Forte said that you could look at “ZIP codes with predominantly queer populations" to try to make some guesses, but, “We’re not making extrapolations when we don’t have the data. … We’re limited to the data that is available within the census, and the environment where our researchers work.”

This article is part of a national initiative exploring how geography, policy, and local conditions influence access to opportunity. Find more stories at economicopportunitylab.com/ .