Feb 14

Kilts, Callbacks, and Contemporary Reimaginings: Ethan Stiefel on 'Spirit of the Highlands'

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 10 MIN. SPONSORED

August Bournonville's classic 1836 ballet "La Sylphide" tells the tale of James, a Scottish Highlander about to be married to his fiancée, Effie. When a sylph – a kind of nature spirit – enters the scene, however, she effortlessly enchants him, and James becomes enamored to the point of forgetting all about Effie and setting out into the woods to find the sylph – leaving Effie open to the romantic advances of his best friend, Gurn. The magical meddling of a witch called Madge adds more spice to the ballet's potent brew, and events charge (or rather, pirouette) toward a climactic ending.

Bournonville based his opera on the 1832 work of the same name by Filippo Taglioni. Originally intending to remount Taglioni's work, Bournonville found that the score, by Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer, was too expensive. He was then determined to create a new work with a fresh score, which he commissioned from Herman Severin Løvenskiold. In the years that followed, Taglioni's original was lost, and Bournonville's version survived, remaining acclaimed to this day.

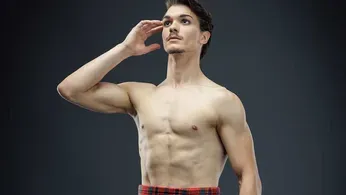

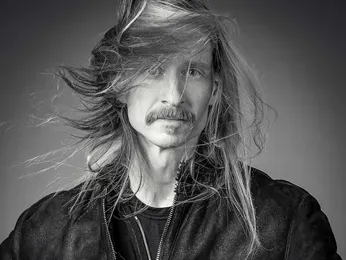

Now leading ballet dancer and choreographer Ethan Stiefel, the Artist in Residence at the American Repertory Ballet in New Brunswick, NJ, brings his own touch to the romantic classic. Stiefel reimagines James as a member of his own ancestral clan, bringing personal resonance to a work that has stood the test of time, and creating a fresh choreographic take that embellishes classical ballet with traditional Highlands dance. Retitled "Spirit of the Highlands," Stiefel's contemporary adaptation is scheduled to run March 7 – 9 at the New Brunswick Performing Arts Center, with dancer Andrea Marini in the role of James.

Read on to discover the compelling draw of Bournonville's enduring work, the personal meaning of the ballet for Stiefel and his focus on authenticity, and why ballet remains a vital part of the American cultural landscape.

Source: Harald Schrader Photography

EDGE: Is this ballet's story a fairy tale warning us about not getting sidetracked from our family life by ambition? How do you see this?

Ethan Stiefel: I think it's just the fantastic world of ballet. From a pure entertainment perspective, having that kind of mystical, magical element speaks to the Romantic period – but even looking at things today, that it kind of has an otherworldly interest, which makes it quite dramatic and powerful.

It could speak to a person going through a moment before they're being married, and, some would say, essentially having cold feet. In this interpretation she is there in front of him, but some people have felt, "Oh, is this just fictitious and in his mind," and it's just something that then has entered into his psyche because he's having second thoughts and doubts in terms of the marriage.

In terms of storytelling and theatrical production, I put those things out there in a form that will tell the story clearly and be accessible, yet maintain the sophistication that people expect from a classical ballet. Call it accessible sophistication, if that makes sense.

EDGE: This ballet is a new version of the August Bournonville ballet, in which James wasn't James Munro; he was James Ruben. But you are descended from Clan Munro, so you're personalizing the work by using the name Munro, as well as calling back to Highlands dance in your choreography.

Ethan Stiefel: I appreciate that you acknowledge that. About a year and a half ago, my father passed away. There was a lot of talk about family, and my mom had been to Scotland twice. Her mother was a kiwi from New Zealand, but her mother's ancestors emigrated from Scotland to New Zealand. My mom did all the homework – went into public records offices, and also spoke to the [clan] chieftain. We can trace our lineage on my mom's side very directly.

I had thought a lot about "La Sylphide" and maybe doing a staging drawing more upon highland dancing. And that was prompted by my coming into contact with Kendra Monroe, who is a highland dance teacher. Both my wife and I happened to take an open class at Carnegie Hall and met her there, and I went, "Wow, there's a lot of similarities [between Highland dance and ballet]... they're different forms, but there are a lot of things that cross over."

Source: Harald Schrader Photography

Then, as I'm sitting there with my mom, I go, "You know what? I think we could do something very cool in terms of the design, in giving it an authenticity as well as a cohesiveness, by setting it within the Clan Munro." In other productions the costumes would be created simply based on what one thought might look good, or whatever the designer, or director, wanted to take on as their aesthetic approach.

Within the Munro tartan there are different color variations. It always has to be the same pattern; that's what defines it as the Munro. But over time, there's a Munro ancient, there's a Munro modern, there's a Munro old and rare, there's the Munro muted. Then there's the hunting tartan, because the Munro tartan is a bright color; that is actually from the famous Black Watch regiment, which you would recognize immediately. It's a dark green and a dark blue. There's six or seven color variations. I thought, "What's cool is we can actually set it within an actual family, and it just happens to be mine."

EDGE: Can you say a bit about adapting the classic Bournonville ballet for today?

Ethan Stiefel: I said, "Look, the Bournonville ballet is kind of the gold standard. There's two productions. There was one that was made earlier than the Bournonville. That and [the Bournonville] are productions that [still] exist and people are familiar with." I wanted to maintain what specifically makes the Bournonville so charming and timeless from the ballet perspective, so I've kept the movements and the sequences of, especially, the lead sylph, and the sylphs faithful in general.

The second act diverts are very much within that Bournonville realm, but at the same time, in Act One, I decided to lean in further in terms of that crossover between ballet and Highland technique. We even share some of the same terms between Highland dance and ballet. We share the fact that we turn our legs out for different reasons: The highlanders did it because the kilt falls better and moves better if your leg is rotated out. Then [there are] all of these things that magically are inherent in each dance form. I said, "Why don't I lean into that further and use actual steps or sequences that you would see in Highland dancing or in today's modern Highland dance competitions?" I think that's what's going to make it really special.

The other thing that I would say is unique to this production, besides the cultural appreciation approach that I have from my personal investment in it, is the taking of the mime and naturalizing it a bit more and making our ballet language a little bit more clear and relevant to audiences of today. It's still a ballet, but that's where I really do feel the Bournonville ballet technique, as well as Highland dance technique, work together in terms of their buoyancy, their vibrancy – it's kind of magical. This will be a production like no other.

Source: Harald Schrader Photography

EDGE: How easy or difficult is it to choreograph a ballet when the principal male dancer is pretty much only costumed in a kilt?

Ethan Stiefel: I mean, I love it. Last week I was in my kilt in New York because it was Burns Night. Robert Burns is a famous Scottish poet, so the best way I could describe Burns Night is that it's St. Patrick's Day for Scottish poet Robert Burns. You know, he was quite a cheeky poet.

By the way, you do feel different when you're in the kilt. It is an adjustment, but I love it. The wonderful thing is how the kilt moves, [which is] why Highlands dancing technique is the way it is. The kilt is a little bit heavier than just wearing tights, or more contemporary costumes and pants, which are usually a bit more lightweight. Wearing a wool kilt, even though we have a lightweight wool, is an adjustment, because you turn slower and there is a little bit more weight. But what's really cool is you get the magic of the kilt having its own life.

Within that, I'm staying generally true to many of the iconic variations and set pieces of the Bournonville, which has worked so well for a long period of time. And then the fact that I'm drawing upon authentic Highland dance, it actually almost takes care of itself, in a way.

EDGE: Are you creating a fresh vocabulary versus relying on an established balletic vocabulary of movement?

Ethan Stiefel This one's a challenge. I know the ballet well from when I performed it, so that's a good reference point. But what I tried to do is revisit the ballet in many different forms – but not too much, so I could also leave room for me to fall into, let's say, accidental interpretation.

The Bournonville mime is very specific to Bournonville, but also very specific to ballet mime of the 1830s, so I want to take that base and build off of that and evolve from that and do it in a way that makes sense within the context of the ballet, but also the context of today. I am still, as I said, using some passages from Bournonville, but the trick is to make sure that I capture the essence and draw upon the Bournonville production in the other areas while staying true to making it different – not just to be different, but because I believe in enhancing it. That's complicated.

Source: Harald Schrader Photography

EDGE: Having delved into so much detail and brought so much creativity to this work, what are you hoping that audiences coming to the show will discover and take away with them?

Ethan Stiefel This is essentially an adaptation of "La Sylphide," but I renamed it "Spirit of the Highlands." "Sylph" can be translated as "spirit," so there's a little bit of a double entendre in "spirit of the highlands." I wanted to put that out there to attract people that may not be ballet goers. Whether you are someone familiar with ballet or otherwise, this is a theatrical production that I feel will be accessible and engaging but still present the classic ballet form with the right amount of sophistication.

I feel now, more than ever, people should gather, communicating and sharing ideas; not just looking at a screen or on the internet. I'm hoping this interpretation can broaden our audience, and that people can come in and find shared interests, shared values, and through the course of coming to not just a ballet, but a theatrical event, we could have an open dialog and also an appreciation of what live theater means and what it contributes to a society. I don't want to get on my soapbox, but I feel we're losing sight of that, and people are getting siloed in their own spaces.

I'm just a son of a Lutheran minister and prison warden, who grew up in Portage, Wisconsin. I love the Green Bay Packers, but I don't subscribe to one way of doing things, and I don't know if I'm a Renaissance person, but I certainly don't understand the definition of masculinity that one has to follow. There's no reason that someone like me, from where I grew up, should have become a leading ballet dancer on the world scene. But I go, "Well, why shouldn't I?" That's how I approach it. That's what I'm trying to say.

"Spirit of the Highlands" will run March 7 – 9 at the New Brunswick Performing Arts Center. Tickets range from $30 to $60. ADA seating is available.

Running time is approximately 1 hour and 25 minutes with one intermission.

For tickets and more information, follow this link.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.